Memories of old Hong Kong: British winemaker recalls growing up on Lantau island tea estate in 1960s

Sarah Driver remembers her ‘most wonderful’ stepfather, the lawyer, politician and social reformer Brook Bernacchi, and roaming free in the wilds of his tea plantation

Within the grounds of a former tea plantation, concealed in a corner of the Ngong Ping plateau, in sight of the Big Buddha, Sarah Driver is retracing her childhood. In the 1960s, she and her brothers, Robert and Ian, were the only European children living on Hong Kong’s Lantau Island.

Dressed in a simple blue cotton shirt and shorts, the elegant 55-year-old mother of four grown-up children inspects the rain-drenched bushes that still grow on the gently sloping grounds. “You only pick the bud and the first two leaves, like this; that is what we were taught as children,” Driver says, plucking the tip of a wet branch between her fingers.

“He had the original bushes imported from Ceylon [Sri Lanka],” she says of her stepfather, who in 1949 founded the Reform Club of Hong Kong, which became the de facto opposition to Hong Kong’s colonial administration. “Brook was a barrister and a big political figure in Hong Kong, as well as a thorn in the side of the government,” Driver adds, also pointing out that Bernacchi founded the Hong Kong Sea School, in Stanley, to train disadvantaged young males for a career in the navy, and established numerous other community welfare projects.

A path leads through the shimmering tea bushes to the whitewashed stone house, where Monty, a dog of dubious breed, patrols the terrace. Tea is no longer produced here, but the facility once employed 20 to 30 workers and its product sold in Hong Kong under the Lotus brand. The assiduously maintained grounds and gardens still extend to three hectares, the rest having been sold over the years or acquired by the government as country-park land.

Driver returns to the villa from her home in London whenever she can, although the motivation for her trip on this occasion is business rather than pleasure. In 2010, she and her husband, Mark Driver (both lived and worked in Hong Kong in the 80s), established the Rathfinny Wine Estate near the picture-postcard village of Alfriston, in the southern English county of East Sussex.

“The chalk soil is some of the best in the world for wine,” Mark Driver says of their location, where hills known as the South Downs descend towards the English Channel. “It drains well but the vines still have to work hard.”

The couple’s ambition has been to produce sparkling wine to rival the most famous French champagnes while contributing to their local community. The wine was launched in London in June, and following an exclusive, one-month partnership with the Savoy Hotel London, it began receiving glowing reviews from some of the most unforgiving sommeliers in the British capital.

This month, Rathfinny launched in Hong Kong to similar levels of bubbly enthusiasm.

Although hectic, the Hong Kong wine launch has given the Drivers an opportunity to spend a few days on Lantau, where decades ago Sarah and her siblings spent breaks away from the family home on Coombe Road, The Peak. They would arrive at Silvermine Bay by ferry and – with no road connecting Mui Wo with Ngong Ping at the time – make the bumpy, time-consuming ascent by Land Rover. (Today, the journey can still take 40 minutes by taxi, even with no traffic.)

“I went to The Peak School and then Island School, and we came up here after school on Friday and went back very early on Monday mornings,” Driver says. “We ate hard-boiled eggs for breakfast on the way down.”

Her stepfather’s reputation as an outspoken, grassroots-minded social activist had its benefits, Driver recalls. “All the ferry crews knew Brook because they had been trained at the Sea School, so he always got noodles and eggs for breakfast on the ferry,” she says.

Driver recalls childhood days on Lantau as “wonderfully wild and free”, with horses to ride and adventures aplenty – all mostly unsupervised. “As children we rode all over the plateau and were always being thrown off,” she says. “It felt very isolated during typhoons. We just put up the typhoon shutters, lit candles, and we always played mahjong, for some reason.”

So we put the snake in a wire cage and were all waved off by our parents as we headed out with the wild python in the Land Rover

Driver has written a memoir of those times and is working with her eldest son on a screenplay that a production company has expressed an interest in turning into a television series. She remembers a cobra being discovered inside the house, and another encounter with an even larger reptile.

“One day, the staff found a large Burmese python eating Gum Sing the teamaker’s dog, but Ian refused to kill the snake,” she says of her brother, who later went on to study snake venom as part of his PhD, and is now a scientist based in Geneva, Switzerland. Robert is a lawyer in Hong Kong.

Instead, Ian rescued the dog from the python’s jaws and phoned the local snake expert, who suggested releasing it in the nearby Shek Pik Reservoir catchment area. “So we put the snake in a wire cage and were all waved off by our parents as we headed out with the wild python in the Land Rover,” Driver recalls. “I was probably nine years old.”

Many of Driver’s fondest memories, however, are of her stepfather, Brook Antony Bernacchi, who was born in London in 1922, called to the bar in Britain in 1943 and joined the Royal Marines during the second world war. He arrived in Hong Kong with British liberation forces in 1945 and joined the Hong Kong Bar Association in 1946.

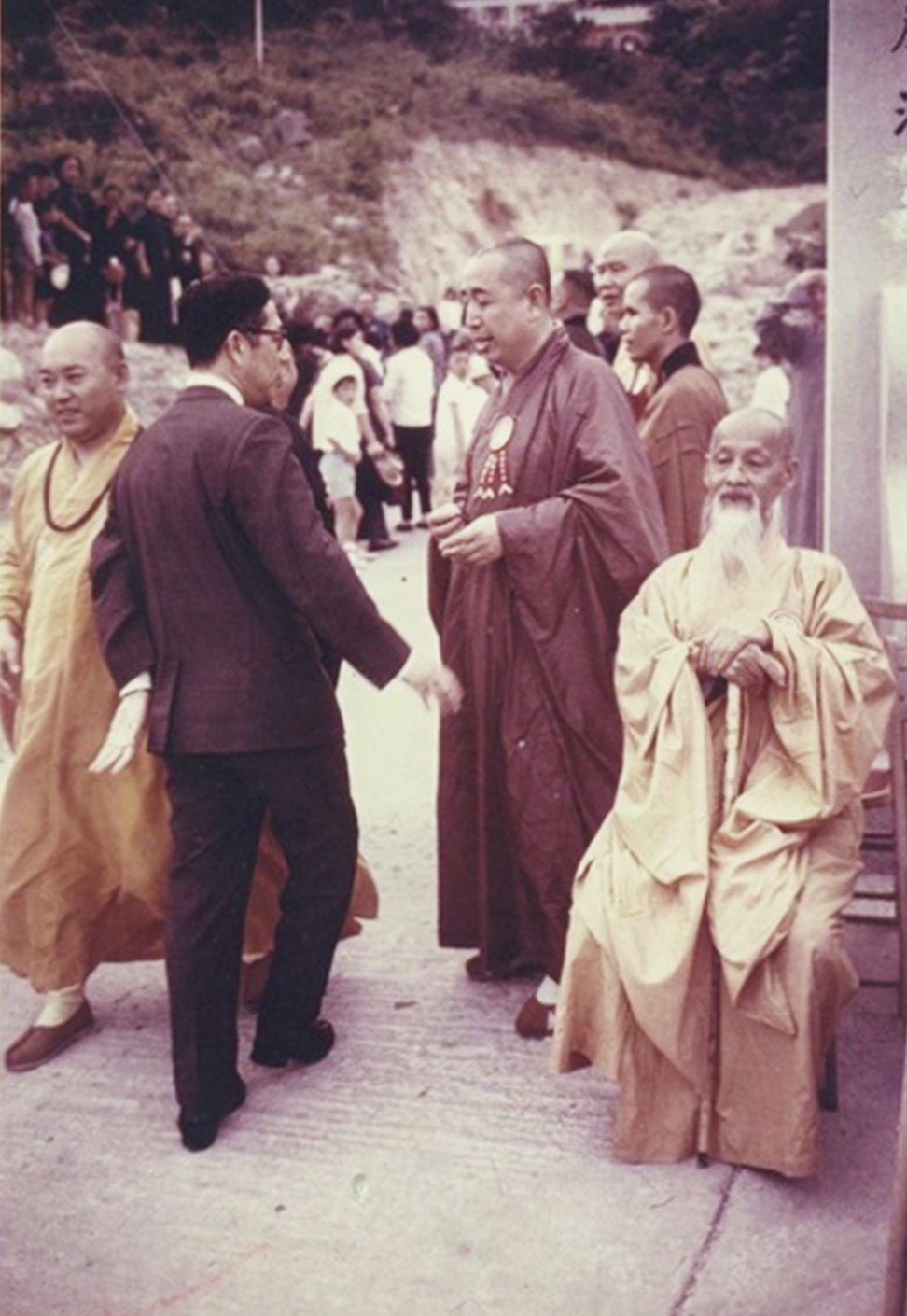

In 1948, Bernacchi became the first Westerner to settle on Lantau. “Brook often went walking on Lantau and sort of discovered the Ngong Ping plateau,” Driver says, recalling stories he told her. “He fell in love with it and became friends with the abbot at the monastery. Three nuns had lived at the nunnery but had died during the second world war. The abbot said it was of starvation.”

The Reform Club became increasingly critical of the colonial administration and what Bernacchi considered to be its disregard for the needs of the Chinese population. He was elected to the Urban Council and campaigned for greater investment in public housing and services, as well as for increased democratic participation.

“My memory is of the phone in the house constantly ringing with the press wanting a comment from Brook on some issue or another,” Driver says.

[Brook Bernacchi] was very engaging and could relate to anyone of any background or race. He had a lot of Chinese friends and he refused to join any club that refused to welcome Chinese members

Bernacchi helped establish other community welfare groups, including the Society for the Aid and Rehabilitation of Drug Abusers, and the Discharged Prisoners Aid Society (in practice, this meant that a number of the staff tending the tea plants were former convicts or drug addicts).

Bernacchi became Queen’s Counsel in 1960, but the following year he was diagnosed with a large brain tumour. Though the tumour was found to be benign, its removal by surgeons at the Royal Masonic Hospital in London left him without the power of speech and paralysed on his left side.

“He regained his speech in the reverse order he had learned it, so for a while he could speak only Cantonese,” Driver says. Bernacchi had often delivered his political speeches in Cantonese.

Despite the semi-paralysis, Bernacchi remained vigorous in community life, and in 1965 he was awarded the Order of the British Empire for public service. “He was very engaging and could relate to anyone of any background or race,” Driver says. “He had a lot of Chinese friends and he refused to join any club that refused to welcome Chinese members.”

In 1979, Bernacchi threatened to boycott Urban Council elections and, in 1981, when the government drew back from a pledge of universal suffrage, he stepped down, saying he wanted “no more to do with it”. “How can one purport to represent nearly six million people in Hong Kong when you have been elected by only 6,000 voters,” Bernacchi asked rhetorically, more than three decades before the “umbrella movement” posed a similar question.

Another cause supported by Bernacchi was the Hong Kong Society for the Blind. When Driver’s biological father, John Whitehead, died unexpectedly, in March 1969, her mother, Patricia Sheelagh Heath, who taught English to blind students, requested that donations be sent to the association in lieu of funeral flowers.

As a thank you, a dinner was arranged and Heath and Bernacchi met for the first time. Soon afterwards, he issued an invitation for Heath and her children to visit All-Knowing Lotus Villa. Driver remembers that weekend well.

“My first impression of this place as a child was lots of dogs,” she says. “We were met at Silvermine Bay by the driver, Ah Yau, wearing a cloth cap and driving an old jeep. I was maybe five or six years old.”

The courtship, Driver believes, was rather unconventional, with Bernacchi perhaps motivated by a paternalistic and protective instinct rather than purely by romance. “I think part of his motivation was to save us,” she says. “He had a profound sense of justice and social philanthropy. I think their love grew later.”

Driver says Bernacchi proposed to her mother just before the bereaved family left Hong Kong for England in December 1969. “I would say Brook wooed us, rather than my mum,” she says. “He used to send us audio tapes with news from the estate. It was normal stuff about the people, how the cook had forgotten to serve potatoes at Christmas dinner, why the goat had escaped, how the dogs were doing, that sort of thing. I think he just wore her down with his loveliness.”

The couple married at London’s St Paul’s Cathedral in April 1970, and returned together to Hong Kong.

Driver remembers a stream of famous faces dropping by the Lantau villa, and she rattles off a list that includes Hollywood film star Danny Kaye, British politician Paddy Ashdown, Reform Club firebrand Elsie Elliott (to become better known, after her second marriage, in 1985, as Elsie Tu), current pro-chancellor of Hong Kong Shue Yan University Henry Hu Hung-lick and Hong Kong governor (1971-1982) Murray MacLehose, among many others.

“We all admired Brook. He was the most wonderful father but he never tried to take the place of our real dad,” Driver says, walking to the traditional English garden, which is planted with powder-blue hydrangeas and red hibiscus. She points to an area of lawn shaded by a tree.

“We scattered his ashes here. There is a small shrine we installed after he died, in 1996. The staff say they still see the occasional gift left for him by local people – usually some fruit, but someone once left a bottle of whisky.

“It is one of my greatest regrets that my own children never grew up to know him.”

Inside the Lantau villa, it is as if the clocks stopped long ago, on an enchanted summer’s day when three children ran wild in the grounds of a tea plantation. There are family photographs, with their mother and Bernacchi, above the fireplace, a set of dusty, cut-glass decanters and an old bearskin draped over the back of an armchair. To one side stands Bernacchi’s large, hardwood writing desk. You almost expect him to appear at any moment, offer a drink and insist one stays for lunch.

“His principle was that no human being was all good or all bad, but that we all had a bit of both and were something in between,” Driver says, recalling how islanders would pop by, asking for help with a problem. “Brook had this vision of the tea plantation that was similar to Mark’s vision of the winery in Sussex; it parallels our sense of local community.”

This autumn, Driver adds, more than 400 people will be involved in the grape harvest at the Rathfinny Wine Estate and most of them will be local.

Not far from the estate, the distinctive Seven Sisters chalk cliffs have become a popular destination for tourists from Asia, and Chinese visitors are occasional paying guests at the winery.

“Staff at the tea plantation were considered to be our extended family, and I feel the same way about the team at Rathfinny,” Driver says. “Everyone feels invested in the project and we support local produce and businesses. Brook had an adventurous ‘can do’ spirit, which we also needed for Rathfinny, particularly in the early days.”

Bernacchi’s Italian-born grandfather, Angelo Giulio Diego Bernacchi, was an entrepreneur who founded a vineyard in Australia, in the 1880s, so wine is something of a family tradition.

“Something must have brushed off,” Driver says.

Wine country? The terroir of England’s South Downs

The Rathfinny Wine Estate, located in the chalky South Downs of Sussex, in southern England, was established in 2010 by Sarah and Mark Driver. The couple – she formerly a city lawyer, he a hedge fund manager – began bottling in May 2015. On an 85-hectaresite, the winery now has more than 300,000 vines planted, mainly pinot noir, chardonnay and pinot meunier, for sparkling wines, and pinot gris and pinot blanc, for still.

Once something of a joke when it came to wine production, England is responsible for an increasing number of quality sparkling whites. The industry in the country as a whole is forecast to grow from the six million bottles it produced last year to 40 million bottles by 2040, and the area planted from 2,500 hectares to 18,000 hectares over same period. More than two million vines have been planted this year alone.

Climate change is helping, with longer, hotter summers benefiting British grape growers, and the South Downs – a hot spot for vineyards – further profits from having a terroir similar to that of the Champagne region of France. A protected designation of origin (similar to the French appellation d’origine controlee) certificate has been registered, protecting the name Sussex and ensuring the quality of any label covered by the PDO.

It was a wine from the South Downs – Ridgeview’s Grosvenor 2009 brut – that Buckingham Palace officials chose as a sparkling aperitif for the state dinner for Xi Jinping, hosted by Queen Elizabeth, during the Chinese president’s visit in 2015.

Rathfinny is 45 minutes from Gatwick airport and the estate is popular with walkers as well as wine enthusiasts, offering tastings and vineyard tours. Modern British seasonal fare is served at the newly opened fine-dining Tasting Room restaurant and accommodation in the middle of the vineyard is provided by the Flint Barns B&B.

Rathfinny produces four principle Sussex sparkling wines – rosé, blanc de blancs, classic cuvée and blanc de noirs. The first two can now be ordered at Hong Kong restaurants such as Arcane, Bo Innovation, Wagyu and The Continental. Staff reporter