Chengdu is blossoming as China's ‘park city’, but its residents pay the price of beautification

- Urban planners hail the approach to environmental protection adopted by the capital of western Sichuan province

- But mass demolitions and relocations have made the plans for urban renewal unpopular with some

“The goal is that every 300 metres you see green,” says Chen Lan, an expert in urban design and planning at Sichuan University, in Chengdu. “You open a window, you see green, you see a park …”

With its mild weather, tea-houses, quiet leafy streets and internationally known food, Chengdu, in southwest China, has long been rated one of the country’s most liveable cities.

What to do on a Chengdu trip – it’s not all pandas and spicy hotpot

For much of its 2,000-year history as an administrative and agricultural capital surrounded by good land, Chengdu thrived in relative isolation. Over the last two decades, though, it has experienced a burst of rapid growth, fuelled by Beijing’s “Go West” policy encouraging development in interior cities.

In 1998, the city was home to 4.2 million people, according to United Nations estimates. With migrants pouring in from other parts of the province, that figure is now 8.8 million, and the latest UN forecasts predict more than 10 million will live in the urban agglomeration by 2026. Official Chinese data, which tends to include rural areas too, puts the current population at 16 million.

To deal with that growth, Chengdu city planners have made environmental protection a focus. Some liken the programme to England’s garden city movement, which emerged in the 1890s to counteract urban crowding and pollution.

But Chengdu’s urban renewal campaigns, like those of many Chinese cities, have resulted in mass demolitions and relocations – and critics say these projects are more about local officials inflating economic statics, impressing Beijing to climb up the party ladder, and creating a pretext for transferring public funds into private hands.

Rather than building parks in a city, the idea is to build a city within a park, according to Chen. By 2050, Chengdu will be home to what local officials say will be the world’s largest network of paths for people to walk or bike. The Tianfu Greenway is planned to stretch 16,900km around the city, and will be linked to hundreds of parks, gardens and protected “ecological zones”, enveloping Chengdu in one massive garden. Some 1,585km had been completed by August last year.

Existing parks will be expanded. Motorways, flyovers and bridges will be “greened” with flowers and plants. One of the new parks, the Longquan City Forest Park, to the east of Chengdu, will be among the world’s largest, spanning 1,275 sq km when it is completed in 2035.

Officials are also trying to preserve the rural outskirts of Chengdu. By 2022, 1,000 farming villages, known as linpan, will be protected. Decades of urbanisation have emptied out these ancient agricultural settlements, which are unique to the region.

“Chengdu is one of the most advanced cities in China – it’s one of the ones that are making environmental protection, public space and quality of life as the agenda,” says Salvatore Fundaro, of the urban planning and design branch of the UN Human Settlements Programme, who has been working on projects in Chengdu.

The goal of these projects is to help Chengdu compete with Beijing or Shanghai while protecting it from the kind of urbanisation and development that has stripped some Chinese cities of their character. Chengdu, an early centre of Taoism, is known for preserving traditions in a way other urban centres have not.

Chengdu is one of the most advanced cities in China – it’s one of the ones that are making environmental protection, public space and quality of life as the agenda

Chengdu’s campaigns have gone through various iterations and names – “garden city”, “rural-city reunification” and now “park city” – but their various iterations have always been inextricably linked with politics.

Li Chuncheng, the former mayor and a top party official, first promoted the idea of Chengdu as a “World Modern Garden City” in the early 2000s. After he was arrested in 2012 over corruption, the term “garden city” fell out of favour.

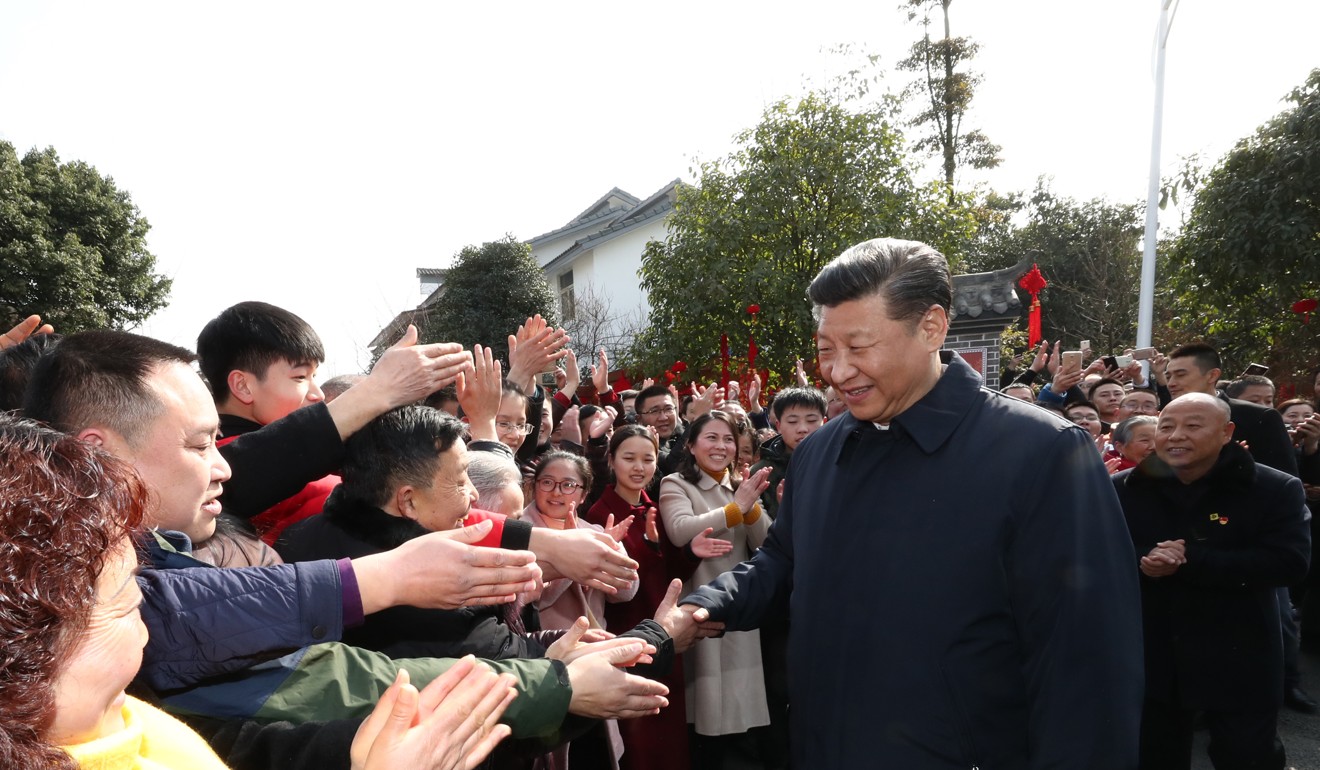

Last year, President Xi Jinping visited Chengdu and praised the concept of the gongyuan chengshi, or “park city”. Since then, Chengdu officials have accelerated the project.

“Every word of ‘gongyuan chengshi’ has its meaning,” Huang Wei, of the department of major projects and public facilities of Tianfu New Area, one of the city’s new districts, told Chinese media in September.

“‘Gong’ indicates something everyone can share; ‘yuan’ refers to ecology …; ‘cheng’ means the place to live with functions like transport, health care and education; and ‘shi’ represents production, a driving force for a city’s development.”

But this development has consequences. One of Li Chuncheng’s nicknames was Li Chaicheng, a play on his name that means “tear down the city”.

“There wasn’t any attention paid to the needs of the people and how these projects could positively affect people’s lives,” says Jiang Xueqin, a Chengdu-based writer and expert on education. “Just because Chengdu puts up an international arts centre doesn’t mean international artists will come to perform and people will become more cosmopolitan and sophisticated. Urban planning really ought to be about improving public spaces so that people interact with each other more.”

Local residents have also been a casualty of the “park city” push. Zhou Wenming, 48, is the last holdout among more than a dozen families who have been persuaded to leave an area on the eastern side of the city that developers are turning into a park.

It is already under construction, with mounds of dirt jutting into the small garden that he and his elderly parents use to grow vegetables. His plot of land, which has been in his family for at least four generations, will be turned into a basketball court.

This has nothing to do with the people. It only benefits the property companies who build houses on or around this land. It doesn’t benefit the people at all

“This has nothing to do with the people,” he says. “It only benefits the property companies who build houses on or around this land. It doesn’t benefit the people at all.”

Zhou is not opposed to leaving as long as legal procedures are followed, like providing residents with legal documents and compensation. So far, local authorities appear to be using pressure to intimidate his family into leaving. Last year, when he travelled to Beijing to petition against the eviction, his wife was slashed by a man on a motorbike. Their windows are regularly broken at night.

Many evictions and relocations happen without the buy-in of local residents. Parts of Fujia village, in the south of the city, are due to be torn down by June this year for construction of a greenway. Yet few residents have heard of the plan. Many are resigned to leaving, and some have already been relocated once before.

“If we have to leave, we leave. There’s nothing we can do,” says one woman, standing outside a mahjong parlour she runs. Across the road is a driving school and next door is a hair salon. Although most of the people here are waidi ren, from outside Chengdu, almost everyone on this street has been here for the last 10 years.

“Of course it will be hard for us,” says the woman, who asked not to give her name for fear of retribution from local officials.

Many residents, though, say Chengdu is one of few cities in China where officials have made a concerted effort to improve the quality of life. People here have access to affordable housing, a good public school system and quality medical care, according to Jiang. The streets are lined with trees and clearly marked bike lanes. Even in mid-December, retirees, parents and children are using neighbourhood parks and walkways. In the larger parks, such as Renmin Park, locals sit in public areas playing chess and drinking tea. Tourists come year-round to visit the city’s panda breeding centre.

In other ways, Chengdu could do more to take advantage of greenery and public spaces residents have already created. Throughout the city there are seemingly random gardens between buildings, strips of land by the side of the road and other unoccupied areas.

Residents, many of them farmers who moved to the city, farm any unused land, growing produce to sell or eat themselves. They organise the land themselves, and everyone sticks to their own plots. “Wherever there is empty land, people will farm it,” says Chen.

Some of these ad hoc gardens are close to part of Chengdu’s green belt project, the Panda Greenway, a pavement running next to the Third Ring Road, a major traffic artery. Cars and trucks whizz past.

The only pedestrian around is Zhang Xiuhua, an elderly woman walking by the gardens. She rarely ventures as far as the greenway because of the dust and pollution from the cars. She was once a farmer, and moved to Chengdu to be with her daughter who works at the local university.

The gardens have been fenced in, a sign they will be torn down. Down the road, green netting has been thrown over another garden. It too will be turned into a park, she has heard.

Zhang believes replacing these garden areas with high-rises and parks is a good thing.

“Development is good for a city,” she says. Asked why, she pauses, looking at the gardens. “I don’t know, actually.”

The Guardian