How Michele Lai came up with Kids4Kids, Hong Kong’s game-changing social enterprise

- The scheme teams teenagers with younger children in local schools and makes them reading buddies

- The organisation empowers those involved by encouraging them to be creative in deciding how to run their sessions

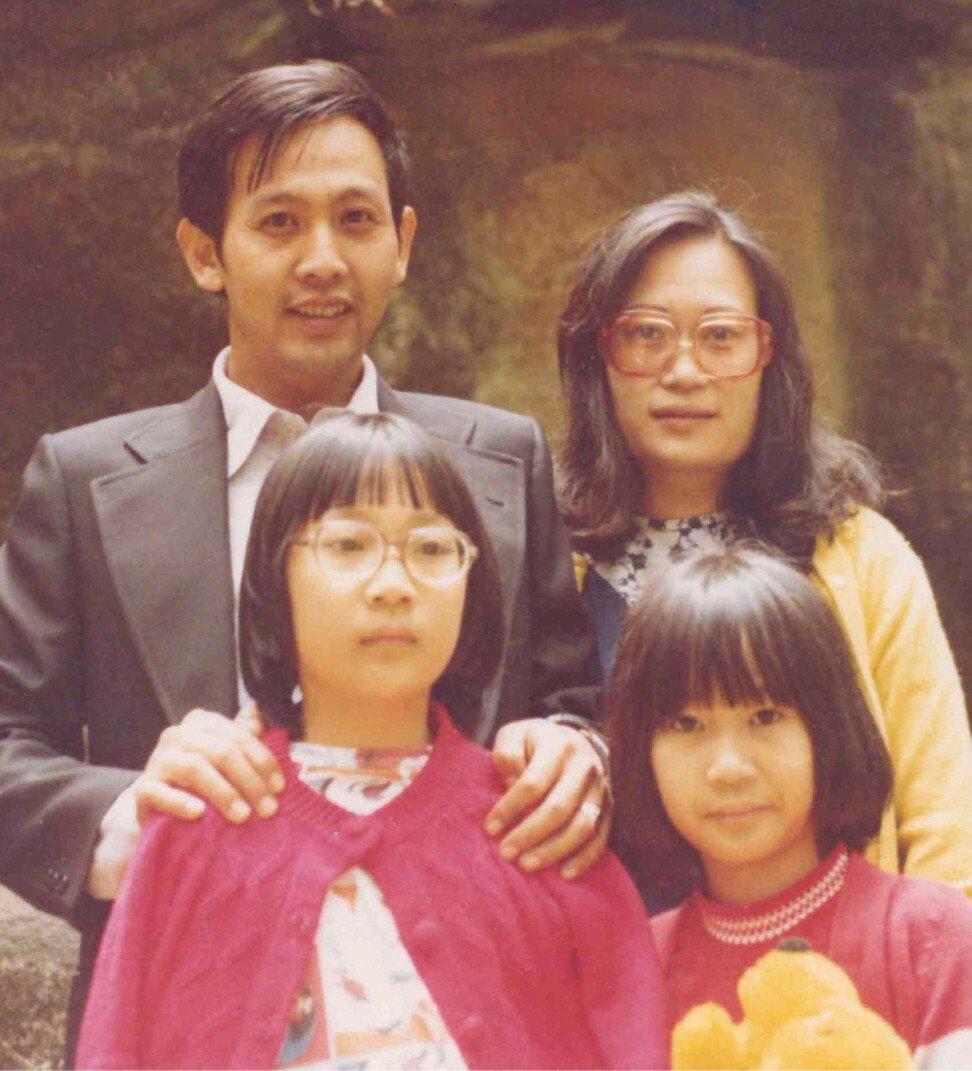

Going south: The race riots in Malaysia, in May 1969, changed the landscape of the country. When I was born, in July that year, a second daughter to my parents, they had already decided they would leave the country at some point for a better future. My father was a marketing director for a car company. We had four domestic helpers and lived a privileged life.

It wasn’t until 1980 that we emigrated to Perth, Australia. My mother found it hard to adapt. She had to do everything herself and was in tears every day. My sister and I helped with the cleaning, but we didn’t know how to cook. We accepted whatever mum put on the table, whether it was baked beans or rice. Dad bought a car dealership north of the city.

It wasn’t a place where there were many Asians. My sister and I went to a public school where there were just two other Asian students. My sister was taunted at school for being Asian and would come home crying. I let racist comments slide off me more easily. In high school I chose easy subjects, like film studies and woodwork, and my parents never objected. When I was older and wanted to get into physics and higher maths I realised I couldn’t. In the end, I did well in high school, but it would have been a struggle to study medicine.

A man’s world: I went to Curtin University, in Perth, to study IT. It was the days of mainframes and really not me, so I switched to marketing. University was the first time I was exposed to a lot of Asians. I spent a lot of time putting on social events for the international student community. Not only did I earn money, it also meant I had some good, practical experience.

I got a job with Toyota Australia and moved to Sydney. Japanese firms are traditionally male-dominated, and I was in a very male industry. After a year, I was moved to product planning and development, the first woman in a non-secretarial position in that department. One of my colleagues suggested I go for my truck licence, so I did. People would do a double take seeing an Asian woman behind the wheel of a truck.

Fast track: I got to know the Toyota team in Hong Kong when they came to Australia for the launch of the Lexus ES300. They said if I ever came to Hong Kong, they’d have a job for me. In 1993, I decided to take them up on it. In Australia, I always felt you moved up the corporate ladder based on seniority; you had to do your time. But in Hong Kong, if you worked hard and proved yourself, you could move fast and succeed.

I was moved around a lot, pulled in to get projects off the ground. I was fast-tracked and led teams of people who were older than me. In 1995, the Hong Kong telecoms industry was going from a monopoly to deregulation. I joined the corporate marketing team at Hong Kong Telecom. I looked after transport and hotels and IT.

Giving things up: My husband, NiQ, grew up in East Timor and moved to Perth. I met him briefly at university, at the events I organised. He came to Hong Kong first and I only really got to know him when I moved here. We got married in 1998. NiQ and I were both working so hard we decided it wasn’t sustainable. Even though I was earning the same money, I said I would give up work, in 2000. Our son JaQ was born in 2002 and Alysha in 2004.

Kids helping kids:I wanted to make sure the kids were socially responsible. I got them involved in making decisions. NiQ thought the kids got too many presents and suggested we didn’t give Christmas and birthday gifts. I explained this to four-year-old JaQ and told him about the children who didn’t have money and couldn’t go to school. He suggested selling some of his toys and books to raise money to give to children in need.

Book buddies: We’ve been doing buddy reading since 2010. Every week we go to 25 schools and community centres to read to kids after school and at the weekend. Eighty per cent of the volunteers are 15- to 16-year-olds, mostly international school students going to read to six- to 10-year-olds in local schools. The kids really enjoy having a big brother or sister.

A psychologist friend sends some of his teenage clients who are depressed. When you start to care about someone beyond yourself, you feel a sense of belonging and community. We have teenage advocates on the leadership teamand for the past five years, our annual two-day youth forum has included teens from less privileged schools. It is very powerful when the community works together and it’s led not by an adult but by a peer.

A rewarding experience: Being elected as an Ashoka Fellow was an 18-month interview process. It’s the Oscars of social entrepreneurship. A lot of people do buddy reading. What we do differently at Kids4Kids is that we don’t give anyone a manual. We give them guidelines and then it’s up to them to be creative and that’s where you get ownership and engagement. If a teenager wants to dress up, bring their guitar or puppets, it’s up to them what they do in that hour. That’s empowering. When you make it controlled, you kill the creativity.

With the Ashoka fellowship, I give talks; I go to Indonesia or Africa and share the idea so people there can take the model and make it work for them. After 10 years of Kids4Kids, we know this model is transforming children in terms of building their resilience and learning about the community. These are things that don’t get taught in school. Don’t beat yourself up about having a privileged life but think about what you’re going do with it.