Opinion | Explosion in Japan’s commercial partnerships shows the soft power on offer in sport

- It’s half-time in Japan’s year of sporting mega-events with the Rugby World Cup behind it and the 2020 Olympics ahead

- The sponsorship frenzy that has gone alongside those events carries a lesson for the world – Japan is still a commercial powerhouse

When South African captain Siya Kolisi recently lifted rugby union’s World Cup trophy in Yokohama, it wasn’t just a significant moment in his country’s history. It was also an important one in the history of the tournament’s host nation, Japan.

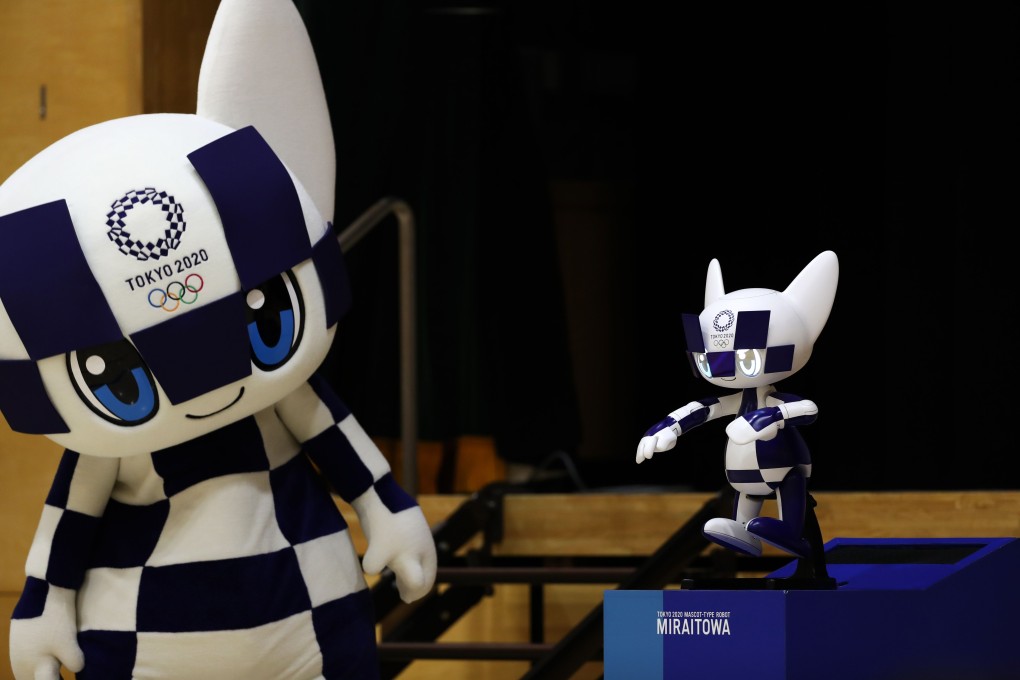

Not only was this the first time that an Asian nation had hosted rugby’s showcase event, it was also something of a coming-out party for Japan’s year of sport. Japan will next be in the global sporting spotlight in 2020 when Tokyo hosts both the Olympic and the Paralympic Games. Hosting two of the world’s biggest sports mega-events in such quick succession reveals something about the country’s sporting ambitions.

Japan’s turn towards sport was embodied in 2011’s Basic Act on Sport, government legislation that now sees it playing the same sporting game as many other countries including China, Qatar and Russia – a contest for soft power.

As in these other countries, Japan faces a multitude of challenges which it believes sport as a policy tool can address. An ageing population, low physical activity levels, health and lifestyle issues, and a need to project cultural and political projections through soft power, are all among the motives for pursuing an ambitious sports agenda.

But there are economic reasons too; the past two decades have seen the Japanese economy slow considerably, not helped by intense overseas competition that its corporations now face from China and South Korea.