Once welcoming, why Germany is wary of Chinese investment amid Trump’s trade war

A China-led wave of company acquisitions has seen Berlin grow leery of granting market access to foreign investors. But fears of an exodus of tech know-how are balanced by a desire to do business on the mainland

Forget US-China trade war tariffs, this is what really worries Asia

Leifeld produces equipment used in the nuclear energy and aerospace industries. Days before that deal collapsed, Germany’s state-owned bank, KfW, announced it would acquire a 20 per cent stake in power grid manager 50Hertz, fending off an offer from the State Grid Corporation of China.

The German government also this month announced plans to lower the minimum threshold to screen foreign investment in industries linked to defence or national security.

Last year the government tightened controls on foreign investments by giving itself the power to intervene if a foreign investor obtained a 25 per cent stake in a German company. Berlin now wants to screen acquisition deals more closely, by reducing that threshold to 15 per cent.

The move comes after a raft of high-profile acquisitions of German companies in the past two years raised renewed concerns of a widespread Chinese takeover of key companies and a loss of technology.

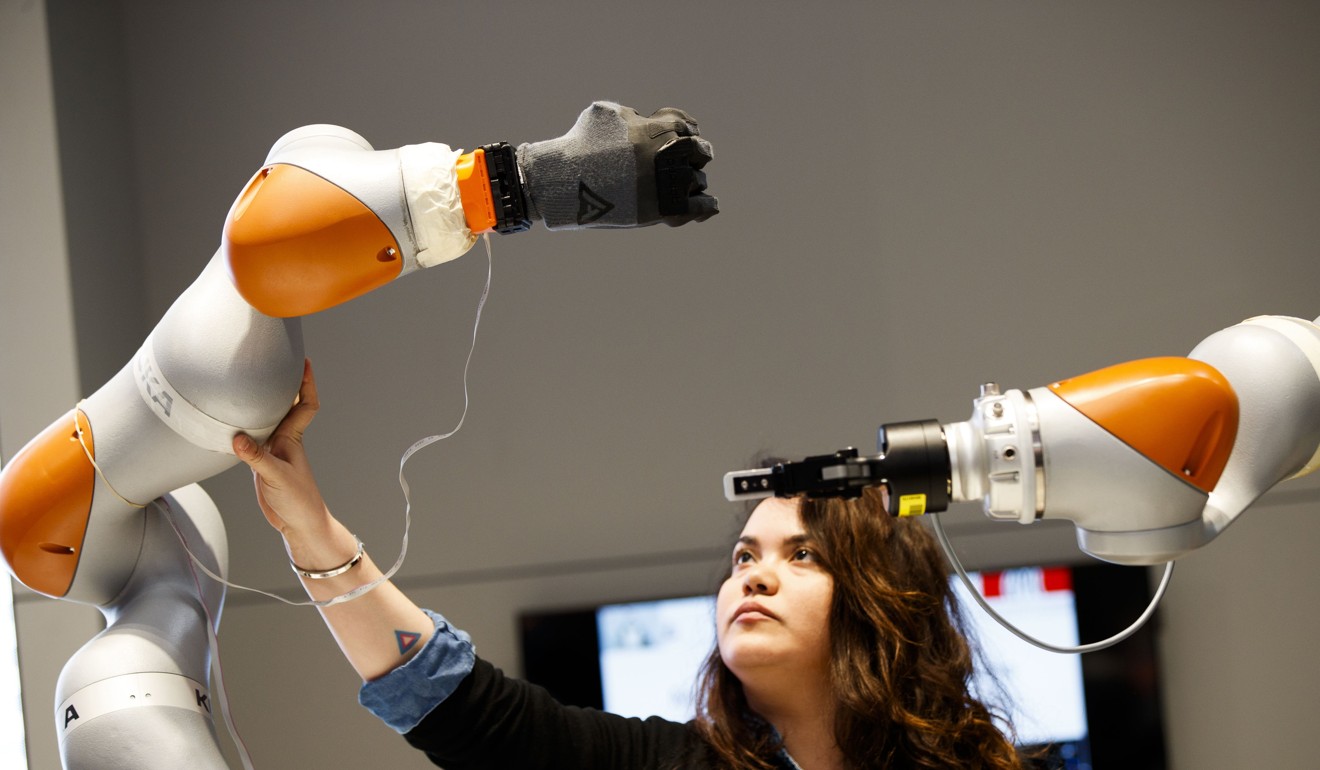

Mergers and acquisitions in Germany by mainland Chinese and Hong Kong companies reached an all-time high of 69 deals in 2017, up from 18 in 2011, according to data from the Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances. The value of Chinese investments in German companies shot up from just €690 million (US$800 million) in 2011 to peak at €7 billion in 2016, mainly due to Midea’s acquisition of robot manufacturer Kuka for €4.5 billion that year.

Forget ‘Made in China’. Say hello to ‘Made in Vietnam’

Apart from Kuka, in the past two years Chinese companies have taken over industry leaders such as Biotest Pharmaceuticals and have acquired vital stakes in German corporate icons such as Deutsche Bank and Daimler, the owner of Mercedes-Benz.

Germany’s “mittelstand” – or small and medium-sized companies that specialise in state-of-the-art technology, and are seen as the backbone of the country’s economy – are feared to be the most vulnerable to Chinese investments, which are often perceived to be more political than economic in nature.

“Although Chinese investors present themselves as private firms, the linkages to government authorities seem to be rather strong. In addition, market access in China to [foreign direct investment] from the EU is still highly restricted,” says Christian Dreger from the German Institute for Economic Research, voicing the common complaint about opaque connections between Beijing and Chinese enterprises, and the lack of reciprocal market access in China.

Dumplings, tai chi and a hint of racism: a Chinatown takes root in suburban Tokyo

Germany and Italy are the two EU countries with the most unfavourable view of China, with 53 per cent and 59 per cent of the population holding a negative opinion, respectively, according to the Pew Research Centre. Britain, with 37 per cent and Poland at 29 per cent have the least unfavourable view.

“The mystery surrounding the management of Chinese companies has damaged its public image in Germany,” says Philippe Le Corre, an expert on China’s relations with Europe at think tank Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The current climate of suspicion surrounding Chinese investments contrasts with the interest they generated during the 2008 financial crisis, which marked the beginning of an upturn in such investment in the European Union thanks to China’s push to internationalise its companies as well as a weaker euro. According to the Mercator Institute for China Studies, Chinese investments in the EU rose from €700 million in 2008 to €30 billion in 2017.

A study by the Bertelsmann Stiffung foundation analysing Chinese mergers and acquisitions between 2014 and 2017 found almost two-thirds of the investments took place in the 10 sectors outlined by Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” drive, which aims to transform the country into a leading industrial powerhouse. New-energy vehicles, robotics, medical, aerospace equipment and new materials are among the target industries. “With Chinese investment, it’s difficult to determine if it is purely a business decision, or if there’s a political motivation, too,” says Cora Jungbluth, the study’s author.

“In the saga of the US-China economic rivalry, ‘Made in China 2025’ is shaping up to be the central villain, the real existential threat to US technological leadership,” Lorand Laskai, of the US-based Council on Foreign Relations, wrote in a recent blog post.

The EU has been similarly vigilant in protecting its technologies. The European Parliament in May passed a proposal to extend the list of “critical sectors” in which the European Commission could intervene in the event of a takeover by foreign investors. The mechanism – backed by economies, including Italy, France and Germany – could be ready by the end of this year.

Macau: the incredible poverty at the heart of world’s richest place

“Without succumbing to protectionism, it is time to show that Europe is not naive in these times of globalisation,” said Frank Proust, the European Parliament’s rapporteur. “We are not against foreign investment, but against strange investment.”

Many business representatives in Germany, however, want their country to steer clear of protectionism. “We don’t want the German government to decide if a family-owned company should be acquired by a Chinese firm,” says Friedolin Strack, managing director of the Asia-Pacific Committee of German Business at BDI, Germany’s main industry federation.

Rather, BDI says, the solution lies in piling pressure on China to open its markets to create a level playing field for Chinese and German companies.

Beijing has repeatedly expressed its commitment to further open its domestic market to foreign competition, and has shown signs of offering concessions. It will scrap foreign ownership limits on local auto firms by 2022, and German media has reported BMW might become the first foreign carmaker to be able to acquire a majority stake of its joint venture even before China officially lifts up investment limits.

But German companies complain about informal restrictions even in industries that are officially open to foreign players. “Despite a change in China’s public messages, we haven’t seen much progress in terms of actual implementation regarding opening the markets yet,” says Jens Hildebrandt, executive director of the German Chamber of Commerce in China.

And, although German business representatives are pro-free trade, the US-China trade war is a helpful tool to gain access to the Chinese market. “We don’t support the trade war … but it helps to create pressure on China to open up its markets,” Hildebrandt says. ■