Is India the new China for start-up investors?

- Indian start-ups are on a fundraising roll, driven by venture capitalists spooked by China’s corporate crackdown and seeking an emerging-market alternative

- Is this the start of a longer term phenomenon as the Iatent Indian market begins to reach its full potential – or are we entering bubble territory?

Investors globally have poured more than US$30 billion into tech start-ups in the first 11 months of 2021, more than double the US$13.1 record set in 2019, according to deal-tracker Venture Capital Intelligence, and there are still December’s numbers to come.

“This year has been a watershed one,” said Pranav Pai, founding partner and chief investment officer at 3one4 Capital, a Bangalore-based early-stage venture-capital firm.

“Globally, investors are very happy, having made serious profits this year,” he said.

“What happened to Didi, that is a very scary, dramatic policy reversal,” said an Indian investment fund head, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

What’s behind the success of Indian tech CEOs in Silicon Valley?

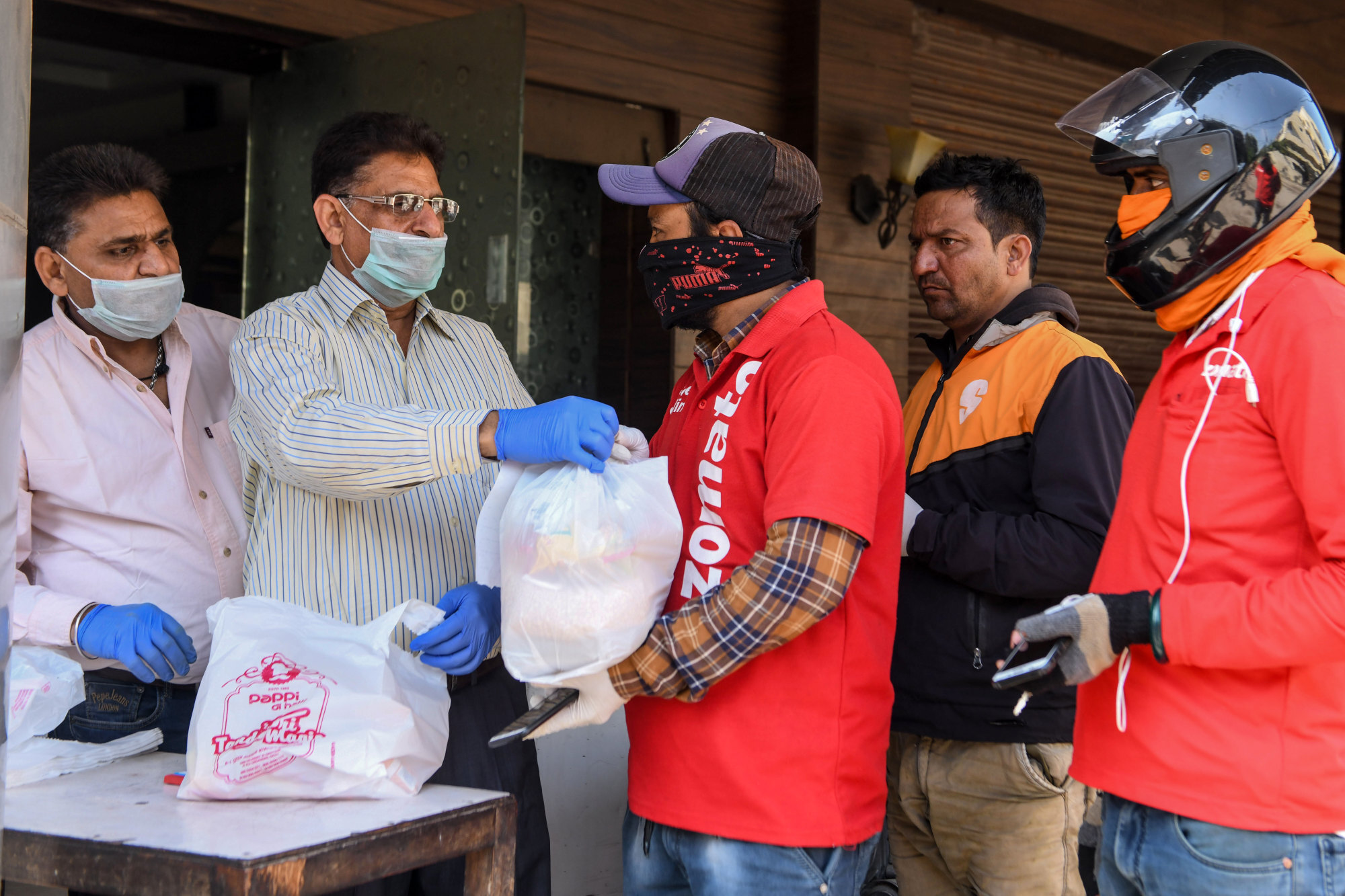

There has also been the tide of cash released by central banks globally to keep economies afloat during Covid-19, some of which has washed up in India.

Another lure for investors has been the vast commercial possibilities from India’s underpenetrated consumer market of 1.36 billion people. (India’s population is expected to overtake China’s by 2030). India has 825 million internet users, which means more than 500 million are still to come online. “There’s such a lot of growth headroom,” said Arun Natarajan, Venture Intelligence’s founder-and-managing director.

IPO boost

Already in 2021, Indian companies have raised a record US$15 billion via IPOs.

It used to be that firms needed to show several years of profits before listing. But the regulator changed the rules to allow loss-making companies to list, making Indian start-ups much more attractive to investors. (Indian start-ups, like their peers elsewhere, are loss-making).

Start-up investors were uncertain about how they could exit. Now, with the IPOs, there’s a clear exit path

“Start-up investors were uncertain about how they could exit. Now, with the IPOs, there’s a clear exit path,” said corporate lawyer Santosh Pai, a partner with New Dehli-based law firm Link Legal who has extensive experience in India and China. “India is now a full-service investment destination,” he said.

In 2020, 18 of India’s then 30 unicorns were Chinese-funded. Gateway House noted that China invested in Indian start-ups when there were no Indian investors. It also provided the “patient capital” required to support Indian start-ups during their loss-making phase.

“I haven’t seen typical VC investors in China do any new deals, although some of them have exited previous investments and achieved good returns. Until the political situation improves, I don’t see new investment happening,” Ntasha S, a co-founder of Venture Gurukool Capability Fund, told China’s state-run Global Times in August.

The Chinese are missed not so much for their money but for their ‘third world’ expertise,” said one Indian fund manager. “They bring a lot of ‘value-added’ experience with their investments. The Chinese start-up experience is more relevant to the Indian situation than the Western model,” he added.

Catching up

In raw numbers, China is still well ahead in venture capital funding. But for the first time, India surpassed China in venture capital funding growth during the first three quarters of the 2021 calendar year.

Venture capital investors sank US$20 billion into Indian companies during the first nine months of 2021, up 147 per cent from the same period in the previous year, tech intelligence firm CB Insights reported. That compared to 101 per cent growth in China where capital investments increased to US$67 billion, CB data showed.

‘There’s a lesson here’: Paytm rout reality check for India’s ‘casino’ IPOs

A number of global investment houses have also been starting to get jittery about the rocketing Indian share market which is up 25 per cent this year. Even India’s central bank is waving a red flag over what it calls the “spectacular gains” by Indian shares that have “raised concerns over overstretched valuations”.

Market risks are rising with a more hawkish US Federal Reserve expected to tighten interest rates to combat no longer “transitory” inflation.

It could be that once the rate-hiking cycle starts and safer investments become more attractive, fund flows could weaken and investors will become more cautious about swollen start-up valuations, unproven business models and profitability prospects.

There could be a valuation “correction”, analysts said. Still, “the Indian market has deepened for all of the start-ups”, said 3one4 Capital’s Pai, adding that India was likely to be “a much larger part of global fund allocations going forward”.