India missing chance to shape WTO’s digital economy ‘rule book’, analysts say

- The US, China and 84 other WTO members have agreed to align their economies in areas such as online consumer protection and paperless trading

- India was the biggest economy to oppose the initiative amid a policy to become self-reliant, but analysts said its move could affect its wider strategic goals

Australia, Japan and Singapore, the co-conveners of the WTO’s joint statement initiative (JSI) on e-commerce, said on Tuesday that after three years of negotiations, 86 countries representing over 90 per cent of global trade had agreed to common rules in eight areas of digital trading, including online consumer protection, electronic contracts and paperless trading.

The eight areas are a starting point with more negotiations on major areas such as data flow scheduled to conclude by the end of next year.

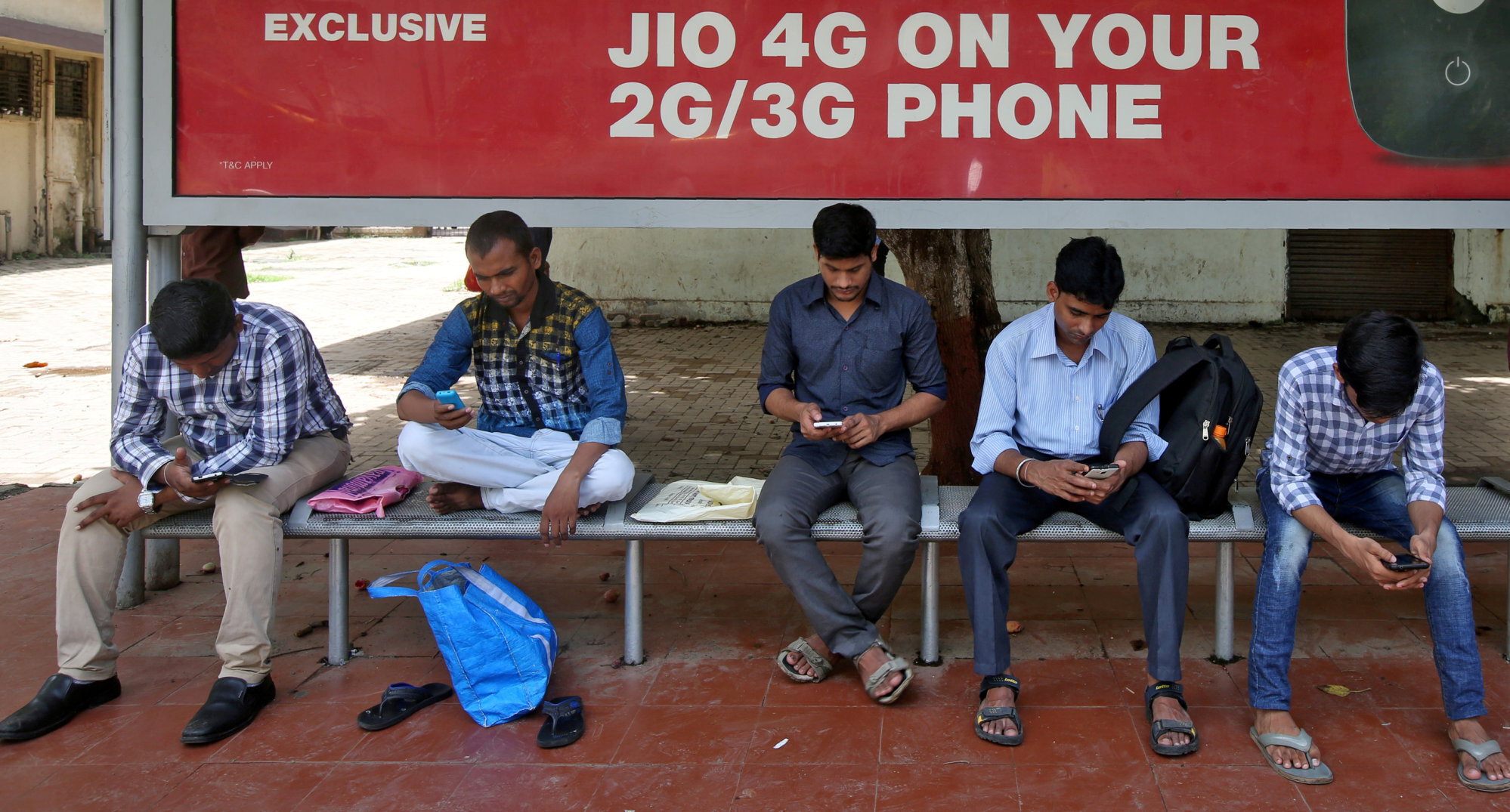

During the pandemic, many countries began relying on e-commerce, accentuating the importance of having “global rules governing digital trade”, the WTO said.

India seeks flurry of FTAs with growth, jobs, China on its mind

The initiative would make business between countries more stable, help to bridge the digital divide and “update the WTO rule book in an area of critical importance to the global economy”, the organisation added.

Where tariffs and customs duties were once the talking points of world trade, the digital economy is now the topic du jour.

On top of traditional trade agreements, countries such as Singapore are increasingly looking to draw up digital equivalents of those pacts. The city state currently has three smaller digital economy deals.

The importance of digital treaties reached a crescendo last month at the G20 leaders’ summit, when China expressed an interest in joining one of Singapore’s deals, the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement, which also includes Chile and New Zealand.

Conspicuously absent from Tuesday’s agreement was India, a major trading member with a growing digital economy. South Africa was another non-participating country.

While the impacts of not being part of the digital agreement on India and South Africa will not be immediately known as the digital treaty still has ways to go and implementation of synchronised digital economies takes time, analysts say there is a chance not being part of a wider digital system can mean these countries miss out on trade deals.

Explaining its resistance over the past three years, India said it wanted to first focus on building its digital infrastructure and ecosystem before locking itself into binding international rules.

Its second point of disagreement was legal in nature. Like South Africa, India says the initiative erodes the integrity of the WTO multilateral framework in that it includes only 86 economies rather than all 164 members.

“However, their staunch opposition did little to stymie the efforts of the JSI, which continued with gusto,” said Arindrajit Basu, research lead at the Centre for Internet & Society, India. “JSI members maintain that the process has been inclusive.”

He said the momentum was growing to regulate digital trade, a far cry from years ago when the discussion of e-commerce was an “obscure novelty”.

Is India the new China for unicorns and start-up investors?

China, which was not an original member of the initiative, joined in 2018 as did Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy which initially had the same misgivings as India.

While India had genuine concerns about wanting to “craft an effective enabling policy ecosystem” over its rapidly growing domestic digital economy, its choice to pass on major global initiatives could leave India out of crucial trade deals in the long run, Basu said.

“India and South Africa have valid critiques of the JSI. However, one must ponder whether the alternatives will further their strategic interests because despite its many criticisms, the WTO continues to serve as a critical forum for the interests of the developing world,” Basu said.

Julien Chaisse, a trade professor at City University of Hong Kong, said however there was a possibility the agreement would not affect India or South Africa’s ability to enter trade deals. Rather it could give rise to two-speed lanes where those in the agreement get fast-tracked, and those who are not end up with slower negotiations, he said.

Commenting on India’s non-participation on Tuesday, Singapore’s Permanent Representative to the WTO Tan Hung Seng said the initiative was bigger than any one country.

“Countries participate in the JSI not just purely for narrow, selfish national interest, but because they want to support the rules-based multilateral trading system,” he said. “The JSI is about building coherent digital rules and robust regulatory framework that can provide businesses with certainty and protection.”

Taking a restrictive approach to digital trade policy will ultimately work against [India’s] own economic interests

Stephanie Honey, a former New Zealand trade negotiator, said participating countries not only gained increased trading confidence but were helping to shape the rules.

“I’d argue that there is value for India in helping to co-design the global rules that will create opportunities for its exporters in other markets and for its businesses and consumers at home,” she said.

“India is already a thought leader and innovator in many areas of the digital economy – taking a restrictive approach to digital trade policy will ultimately work against its own economic interests.”

New Delhi’s aversion to large trade deals comes amid the Modi administration’s push for a “self-reliant India”.

“In the name of openness, we have allowed subsidised products and unfair production advantages from abroad to prevail,” Indian Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar said when announcing the withdrawal.