Malaysia faces pressure to ‘innovate’ chip sector as US-China rivalry gives Vietnam a boost

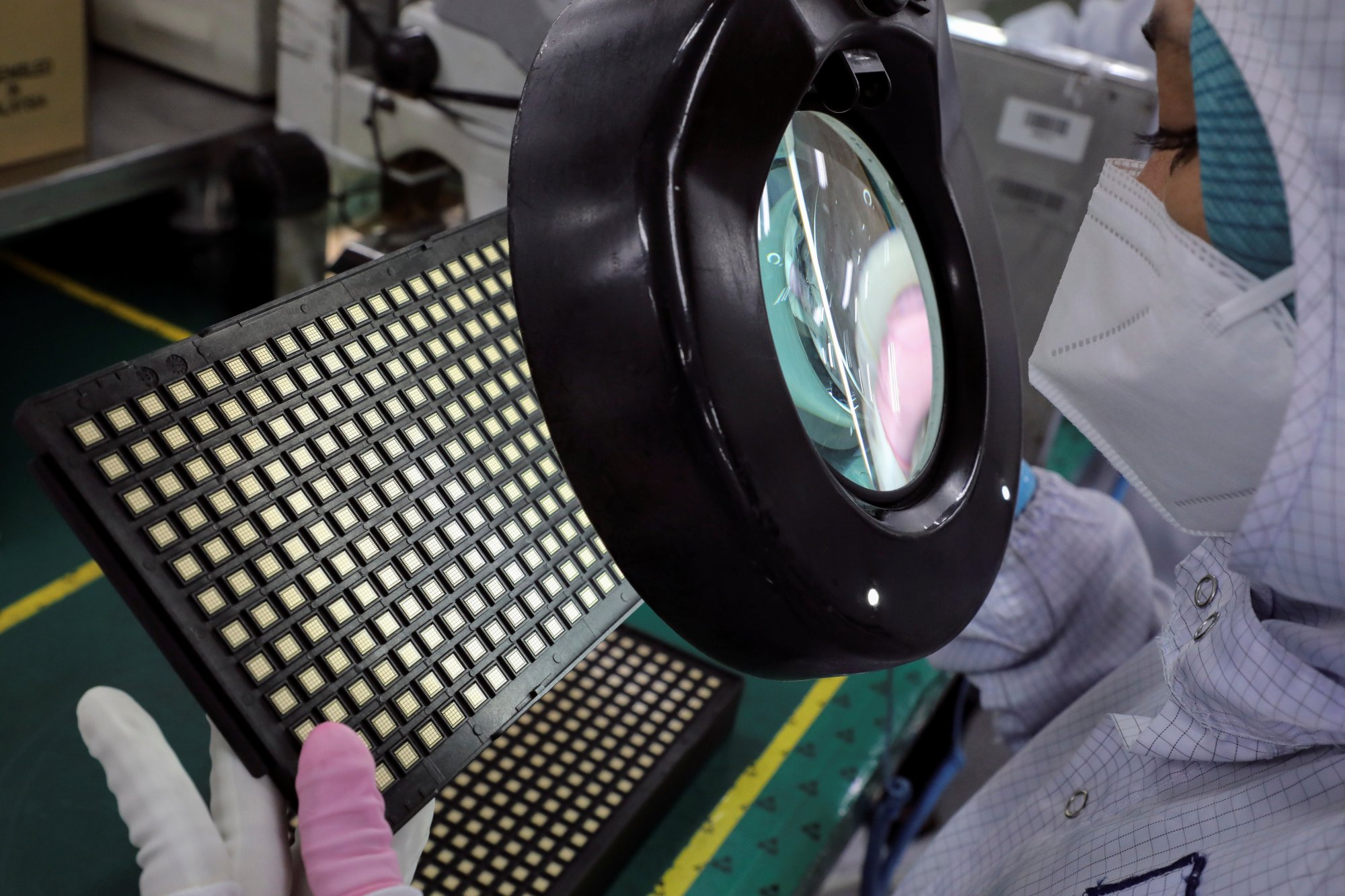

- Malaysia, a key node in the global semiconductor supply chain, supplies an estimated 13 per cent of demand for packaging and testing

- With increasing competition from countries like Vietnam, Malaysia should ‘double down’ on its advantage to stay ahead, say analysts and insiders

The issue hinges on the accusation by the US that China has used information and communications technology built and developed by Chinese firms to engage in espionage and mass data collection, an allegation that China has denied.

But the die has been cast, and companies – including Chinese firms – are making a beeline to expand their operations beyond China’s shores to make sure they can meet US regulatory compliance.

Malaysia is a key link in the global semiconductor supply chain, having built up its local semiconductor industry and ecosystem over the past 50 years to now supply an estimated 13 per cent of demand for packaging and testing.

A separate 2 billion ringgit deal was announced last year by TF AMD Microelectronics – a local partner to Intel’s rival chip maker AMD – to build a new manufacturing facility.

“Malaysia needs to double down on its advantage, really own the back end, innovate and not let anyone sneak up on you,” said Ernest Bower, president and chief executive of political risk consultancy BowerGroupAsia (BGA).

Branching options

Malaysia’s industry players appear to agree. Besides the investments by Intel and TF-AMD, other firms are ramping up their packaging and testing facilities to meet growing demand as more wafer-fabrication plants are set up globally, according to Wong Siew Hai, president of the Malaysia Semiconductor Industry Association (MSIA).

Wong said that expanding Malaysia’s packaging and testing capacity was “a given” if it wanted to at least maintain its global market share.

He said that the local industry expected to grow Malaysia’s total semiconductor export value to around 1.2 trillion ringgit by 2030, double the nearly 600 billion ringgit achieved in 2022 and in line with expectations that the global total export value would hit US$550 billion in the next seven years.

Asia’s ‘prolonged downturn’ in semiconductors to bottom out by mid-2023: ADB

“Why we have to grow [packaging and testing] is because the number of FABs (wafer-fabrication plants) going to be built over the next five years or so is expected to be about 100,” Wong told This Week in Asia.

“So that’s why you see a lot of companies are growing their assembly and testing [facilities]. Some have already started building, some will complete building this year … so I expect expansion to continue to support the growth of FABs, otherwise we will not have enough capacity.”

Malaysia secured a total of 121 billion ringgit in inbound foreign direct investments (FDI) over 2021 and 2022, according to government data.

The semiconductor sector accounted for a sizeable portion of the investments over the past two years, and accounted for 81 per cent of total approved manufacturing FDI in 2021 that far surpassed the historical annual average of 38 per cent, said Arvind Jayaratnam, an analyst with Maybank Investment Bank.

“On this basis, we believe that Malaysia, in fact, outperformed expectations,” he said, adding that the semiconductor sector’s investment performance over the past two years indicated that the country remained “relevant and current” in the global tech supply chain and was an active beneficiary of investments for supply-chain security amid the US-China rivalry.

But MSIA’s Wong said that narrowing Malaysia’s focus to just packaging and testing would be a missed opportunity.

He said the fact that major firms were shopping around the world to find suitable locations to set up new semiconductor-fabrication plants meant that Malaysia had a chance at finally getting a foot into the big leagues.

“If we want to go beyond packaging and testing, we have to get into FABs as well. Wafer fabrication is very expensive, but since so many plants are being built throughout the world, we have to attract them to come here,” Wong said.

Wong said Malaysia should aim to attract at least one company to set up a mid-tier wafer-fabrication plant, which he estimated would cost US$4-8 billion, as the country did not have sufficient experience or expertise to pitch for high-end wafer manufacturing.

“We are advocating to take FDI to set up an FAB … With an FAB, we complete our supply chain,” he said.

IT hub India seeks to chip away at China’s grip on electronics

Lurking competition

But Malaysia is not the only prospective beneficiary of the industry’s supply-chain overhaul.

Further north, investors have been engaging Vietnam to set up manufacturing plants to take advantage of generous terms from the government.

At the same time, US manufacturer Synopsys announced it would deepen its expansion in Vietnam by providing more training and software licences for a chip design centre.

South Korean chip giants dodge ‘worst-case scenario’ in new US proposal

While it was still early days for Vietnam in its foray into the semiconductor industry, the country had all the attributes to get ahead of competitors, said Alberto Vettoretti, managing partner and FDI expert at Dezan Shira & Associates.

He said Vietnam was in prime position to attract manufacturers looking to diversify their supply chains outside China with its relative political stability, competitive labour costs, and proximity to China.

The Vietnamese government has also laid out competitive tax exemptions for investments in the semiconductor sector, and offered to subsidise up to 15 per cent of training costs for companies.

“The Vietnamese government has been pretty adamant about promoting hi-tech manufacturing,” Vettoretti said.

Market research group Technavio expects Vietnam’s semiconductor-manufacturing industry to grow by about 6 per cent annually between 2022 and 2027.

Additionally, Vietnam’s 13 free-trade agreements with various countries were attractive to manufacturers, Duane Morris Vietnam lawyer Oliver Massmann said in a note.

Vietnam has one of the most free-trade deals in the world, and the most in the Asia-Pacific. In comparison, Malaysia had only seven, Massmann said.

China’s loss is Southeast Asia’s gain as supply chains shift

Work in progress

Wong said Malaysia’s value proposition was different from that of Vietnam, which had a much larger population to meet the needs of labour-intensive operations.

Malaysia was looking further up the value chain for higher-quality and hi-tech investments, which Wong said was more important than just looking at the total FDI value.

As a global trading nation, we have to support any country that wants to do global trade with Malaysia

At the same time, Wong said Malaysia would need to balance its engagements with the US and China – both of which were top trade and investment partners – especially if tensions between the two superpowers led to a supply-chain decoupling.

“It’s going to be very complicated, no doubt about that … but we cannot choose one over the other. As a global trading nation, we have to support any country that wants to do global trade with Malaysia,” he said.

But a clear policy direction was also needed to get the government and industry aligned at all levels and ensure the necessary infrastructure was in place to support new investments, said BGA’s Bower.

“The idea to go into mid-level FABs – that are not covered by US export rules – might be a good idea for the longer term. But you need to look at things like talent, the cost of electricity, waste water, industrial gas,” Bower said.

“This has to be a whole-of-country strategy. If Malaysia can execute its strategy, then it can be in the game. But if it can’t, it’s better to call it early.”