Ecologists hope to build Singapore’s first man-made oyster reef

- Man-made oyster reefs have popped up across Australia, Europe and the US but remains a relatively new concept in Southeast Asia

- Scientists say artificial oyster reefs help boost local marine biodiversity, lower pollution in waters and provide food for sea organisms

They pour seawater into the boxes of shells, which are then cleaned and left to dry under the sun to kill any bacteria, ensuring no risk of biohazards or pollution.

Once the “quarantine period” is over, the oyster shells are placed in reef bags made of biodegradable potato starch.

Suited up in rash guards and snorkelling gear, Yokoyama and her team swim a short distance in the sea to secure the reef bags on a jetty’s concrete pillars.

By reintroducing the oyster shells back into Singapore’s waters, they hope that baby oyster larvae will settle on the shells in the reef bags. Over time, the aim is for the oysters to form a hard oyster reef structure. The shells should provide crevices to shelter other marine organisms such as fish, molluscs and crustaceans.

Oyster reefs are among the most severely degraded marine habitats on the planet, reports by The Nature Conservancy show, mainly due to overharvesting, poor fishing practices and coastal developments.

But scientists say artificial oyster reefs have far-reaching potential. They help boost the local marine biodiversity and lower pollution in waters via the oysters’ natural filtering abilities.

They also provide food for other organisms, such as fish, crabs and birds, protect shores from erosion and encourage the growth of other marine ecosystems such as sea grasses.

The idea first came about when Yokoyama’s manager was mulling ways to reduce food waste while working with hospitality partners. Yokoyama is an ecologist at Witteveen+Bos, a leading Dutch engineering consultancy.

Singapore has naturally occurring oyster populations, which can survive in intertidal zones. These hardy rock oyster species are resilient to stresses and changing environments in and out of the water.

Yokoyama and her team saw value in repurposing old oyster shells to make an artificial reef, given that this could be used to augment the city state’s existing oyster populations.

Armed with a seed grant from Singapore’s Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment, the oyster pilot project began in August last year, when Yokoyama’s team started approaching hotels and chefs.

Shell collection began in November, with 5kg to 15kg of oysters sourced each time from hospitality partners such as Sofitel, W Singapore - Sentosa Cove, The Oyster Cart and Joo Chiat Oyster House each time.

So far, preliminary data from their baseline studies has shown promising results, Yokoyama said.

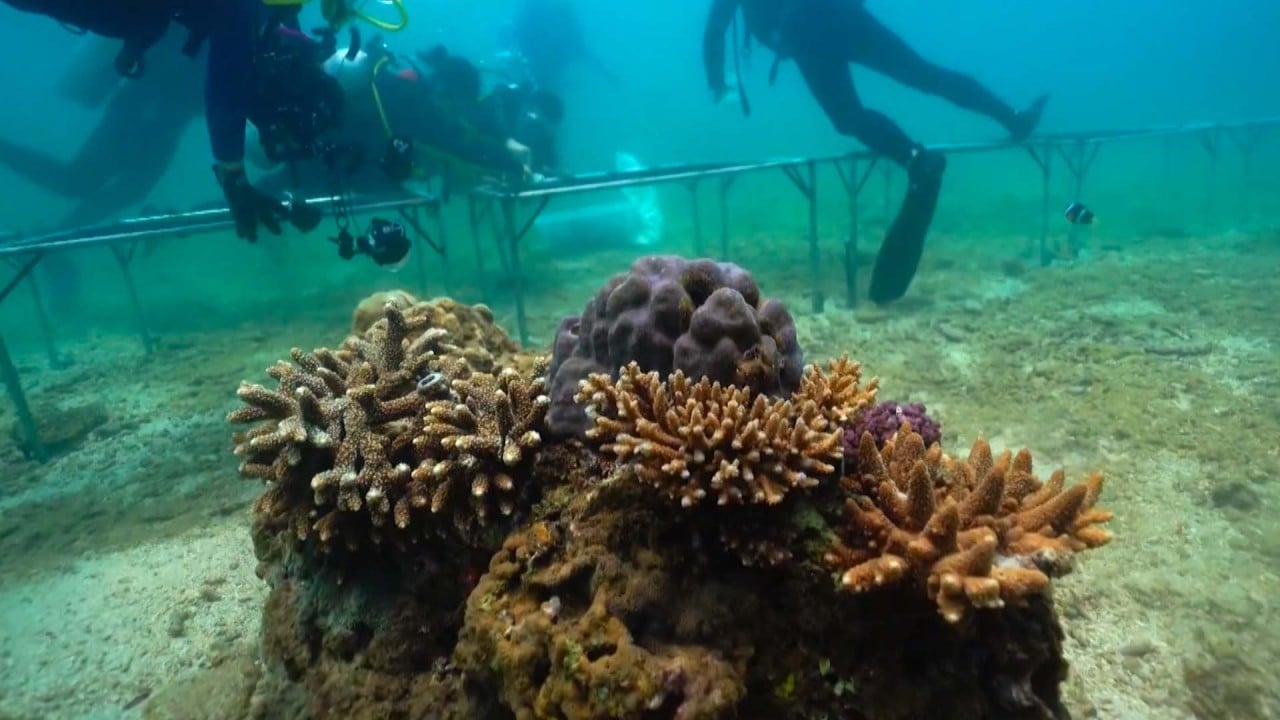

The jetty pillars are already a “rich living sea wall”, with a rich population of shellfish, green mussels, black mussels, predatory molluscs known as drills, nerite snails, sea squirts and coral polyps.

But with the presence of the reef bags, plenty of new residents have taken up residence, ranging from crabs, seen scuttling in and around the reef bags, to goby and other reef fish species.

“The holes and crevices between the oyster shells offer shelter and protection from waves and currents and a safe space from predators during low tide, as compared to a sandy seabed … It’s like a vertical HDB flat for marine life,” Yokoyama said, referring to apartments provided by Singapore’s public housing authority. “A lot of people look at this wall and think it’s very ugly, but it’s all alive.”

Yokoyama and her team were curious to see if the non-native species of oyster shells – typically Pacific oysters – used to attract native baby oysters would also work in Singapore.

Oysters in warm waters are more productive than those in cooler waters, and can gobble up more pollutants and particles to improve water quality. In turn, cleaner water can help other types of ecosystems, such as coral and seagrass, flourish as more light is able to penetrate deeper and promote growth.

To date, the team has collected some 130kg of shells, and plan to attach 30 of their reef bags on the jetty’s pillars.

Oysters reproduce quickly and typically take between 18 months and three years to grow into adults.

This year, the team plans to monitor the shells for six months to see if the oyster larvae mature into adults. They also want to rope in citizen scientists to help with observation and documentation.

Yokoyama acknowledged that the project is still relatively small, but was a “good start”. The team estimates it could take three to five years to see results.

Walking the talk

For some of the team’s corporate partners, the project has provided a platform to practice greater sustainability, and embrace more environmentally friendly and responsible practices.

Among them was W Singapore - Sentosa Cove.

Within a month of the hotel starting discussions with Yokoyama’s team, it had started collecting its first batch of oyster shells. In December, when the team needed 1,000kg of oyster shells, the hotel contributed 26kg despite manpower constraints during the year-end festive period.

The hotel soon realised it needed to broaden its perspective, and came up with a number of “diverse activities” aimed at expanding how it could “contribute more effectively to food waste projects and sustainability”, it said in a statement.

For instance, the hotel offered used plastic bottles to its partner, the Sentosa Development Corporation, to build a road using more sustainable resources. The plastic waste will be converted into new bitumen for road construction.

For restaurant Joo Chiat Oyster House, repurposing oyster shells is not new. It organised candle-making workshops in December, using old oyster shells as a base.

“We had always hoped to recycle our oyster shells to be used as construction material, but we lacked the expertise … To see them being used in the ocean is something new and something we never thought about,” said restaurant co-founder Maggie Chen.

Yokoyama is happy that the oysters are finally getting their turn in the spotlight.

“Oysters are hardy ecosystems. In Singapore there’s a lot of attention on coral reefs and mangrove forests, which are important, but it’s not feasible to implement, because of the tolerance range of where they can thrive,” she said. “Oyster reefs are a good way to complement them, using soft engineering through nature based solutions.”