Nepal’s traditional healers vow to preserve ‘secret and sacred’ indigenous knowledge even as climate change bites

- Climate change and a dwindling number of practitioners pose a threat to the Sowa Rigpa system of medicine that dates back to more than 2,500 years

- The number of practitioners in Nepal, where Sowa Rigpa is not formally recognised, is falling amid limited educational pathways and legal recognition challenges

When a patient visits Tsewang Gyurme Gurung’s clinic, he reaches for their wrist first.

His eyes are closed and his fingers move slowly as if he is shifting guitar chords, while examining for a pulse.

“When we do the pulse reading, we will be watching the frequency and amplitude of vital organs to find out if there are any imbalances,” Gurung explains. “The fingers are our tools, they’re the scanner to the body. Pulses are the messenger to the amchi from that body.”

The ancient practice of Sowa Rigpa is facing an existential crisis in Nepal. There are only about 200 amchi still practising in the country, according to the Sowa Rigpa Association, their numbers dwindling due to limited educational pathways and legal recognition challenges.

In his late-30s now, Gurung has been practising the Sowa Rigpa system of medicine since his childhood. He initially wanted to be a surgeon, but followed the path of traditional medicine after his elder brother showed little interest in continuing their family lineage.

Gurung said he learned about human anatomy and medicinal plants used for treatments from his father, Tshampa Ngawang Gurung. He was diagnosing patients when he was a teenager and is now an 11th-generation amchi based in the remote village of Jomsom, the district headquarters.

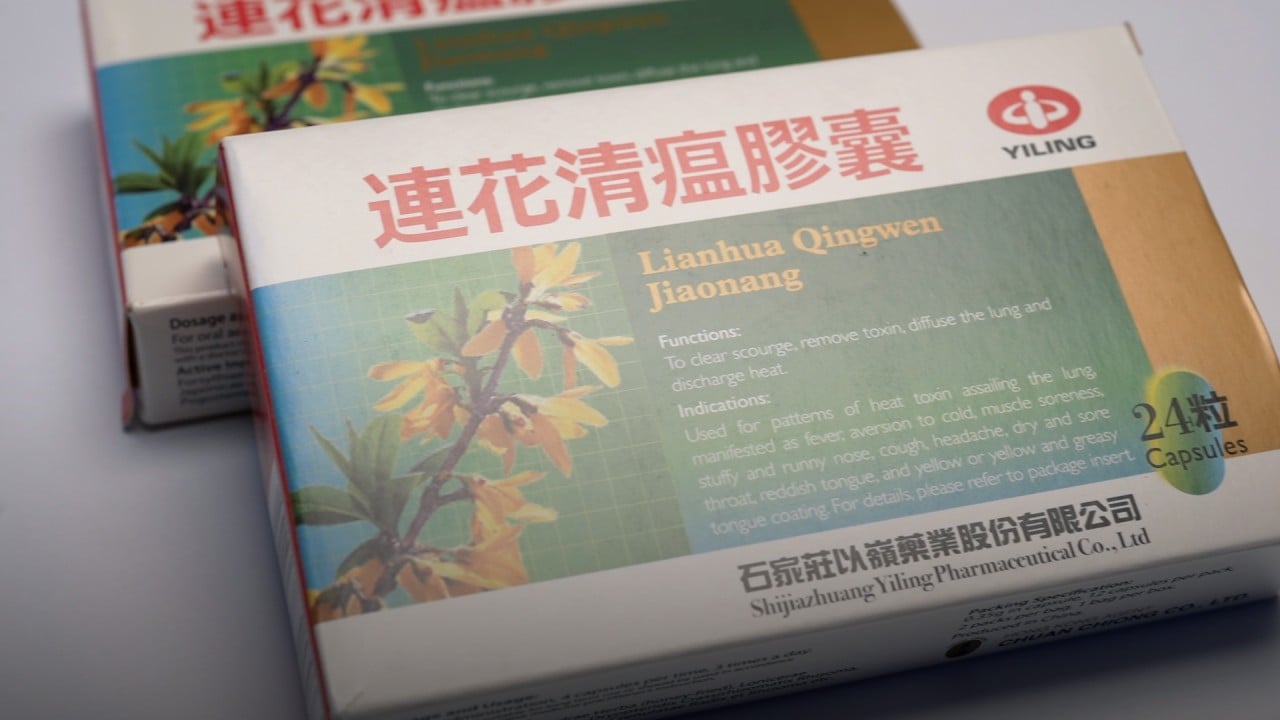

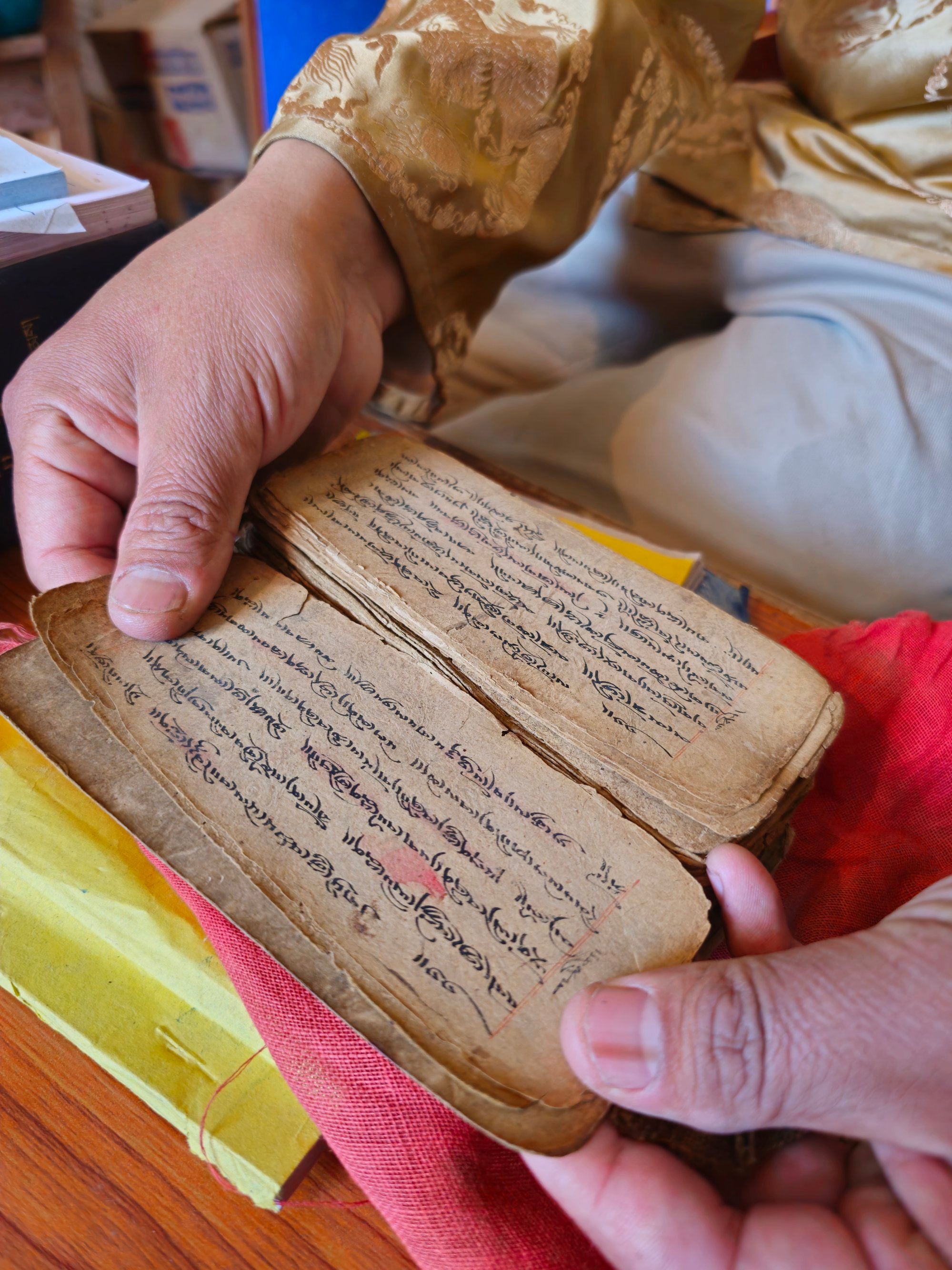

Sowa Rigpa, commonly referred to as traditional Tibetan medicine, derives its knowledge from centuries-old texts that have been passed on from generations of healers. They studied the human body in detail, while also documenting hundreds of plant species that are used to treat ailments, ranging from coughs and fevers to more severe illnesses.

Indian police say snake venom being smuggled for use in Chinese medicine

At his clinic in Jomsom Bazaar, housed on the ground floor of his Dancing Yak Hotel, Tsewang Gyurme unwraps a text book, written by his great-grandfather, covered in a red cloth. Written in Tibetan script under the dim light of a burning incense stick when there was no electricity, he referred to the book as a “red treasure” with “secret and sacred” indigenous knowledge on the science of healing.

For generations, the book has served as a guiding star to treat people in the remote Himalayan regions with little or no healthcare facilities. But even as hospitals and smaller health posts have become available, amchis are still the most trusted medical practitioners in places such as the Mustang and Dolpa regions.

Kunga Gurung, a 36-year-old farmer from Lo Manthang in Upper Mustang that borders Tibet, said he consults a local amchi for common ailments and would only visit a hospital for major issues such as surgeries. He also believes plant-based medicines have fewer side effects than modern medicines.

“Our grandfathers and fathers used to go to the amchi, and we continue to go as well,” Kunga said. “It’s a habit and also the faith we have in them.”

But despite the faith many still place in them, the number of amchis practising in Nepal continue to shrink, in part because there are few opportunities for those who wish to study it but do not have an amchi in their family to learn from.

To fill that gap, Tenjing Dharke Gurung opened the Sowa Rigpa International College in Kathmandu in 2016. The five-year undergraduate degree under Lumbini Buddhist University, founded in the birthplace of Buddha, aims to promote the traditional practice alongside a science-based education.

“This will allow us to save our tradition and move it forward,” said Tenjing Dharke, an amchi in Kathmandu, adding that 17 students have graduated so far.

Though Nepal’s Health Act of 2018 lists the Sowa Rigpa system and amchis as “health services” alongside modern treatments and Ayurveda, the practitioners are not licensed by the Nepal Health Professional Council, which registers “all health professionals other than medical doctors, nurses, pharmacists and ayurveda”.

Sarina Guragain, who oversees the homeopathy and amchi unit at the government’s Department of Ayurveda and Alternative Medicine, said the process to grant licences to amchis was still under discussion. She added that Nepal has not been able to invest in amchis, considering their small population.

However, the department has set standards and allowed local authorities to register amchis so that they can practice in their designated areas.

In Jomsom, Tsewang Gyurme is the only registered amchi who sees a handful of patients daily. Despite a growing number of doctors, he said people still visit his clinic.

“In [modern] medicine, they see the human body a little different than we do, but they have also learned from ancient knowledge,” he said. “The main difference is we use herbal science, which is not about chemicals but compositions.”

Sitting in his clinic, surrounded by herbs and medicinal plants, Tsewang Gyurme shows the raw materials and medications he has prepared in the form of pills and powder. Over the years, he has changed certain compositions, akin to the changes in chemical compositions in modern medicines.

“I have to understand the compositions of the medicinal plants I have in my basket and which to mix,” he said. “So an amchi has to be an expert in pharmaceuticals, too.”

The doctor fighting against India’s ‘deep-rooted’ belief in black magic

Though the primary intention is to heal the needy while sourcing plants, he said they are aware of the need to protect rare and vulnerable species, including the Himalayan marsh orchid and caterpillar fungus, also known as Himalayan Viagra.

Tsewang Gyurme said most amchis only pick the plants they require, replant them and cautiously tend to root medicines so they are preserved for the following seasons.

“To be an amchi, you also have to be an environment lover and conservationist,” he said. “You have to be very near to nature.”

Spring revival: Nepal’s communities lead efforts to preserve water source

But as Tsewang Gyurme is working to protect and preserve the precious plants, the tradition he is holding to may fast be disappearing. He is unmarried and does not see himself settling down soon, raising uncertainty about his lineage of amchis.

However, he said he is not worried and keeps himself busy by researching the ancient practice, along with working on social issues in Jomsom. The amchi believes that there will be a remedy to create a balance, just like how he prescribes plants to fix imbalances in the human body.

“We need colleges and proper licensing for the amchis to thrive,” he said. “As for myself, if I eventually have children, I will pass on the knowledge to them. Otherwise, if anyone else comes to me seeking for knowledge, I will pass on to them. This is another way how lineage is passed on.”