What makes street food clutter in Thailand, heritage in Singapore?

As street food vendors across most of Asia face an unappetising future, Singapore’s hawkers are winning Michelin stars and being put forward for Unesco recognition. That must be one super secret ingredient ...

We’re waiting for the arrival of “Hawker Chan”, as he’s known in the game, and his operations manager Daniel Wee rattles off the number of food stalls they’ve opened in the past two years. “We’ve now three in Singapore, 11 outlets worldwide including the Philippines, Melbourne, Taiwan, Bangkok, and we’re opening soon in Kazakhstan.”

A Chinese veteran hawker in the old Soviet Union? Really? “From the media interest and our investigation, there’s a market for what we do, it’s special,” adds Wee.

The Singapore government agrees. Its famous hawker industry has been thrust into the spotlight since Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced recently it would be nominated for Unesco’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

This effectively means hawker stalls will be enshrined as World Heritage Sites, a development that has brought derision from other countries on the continent, especially in Malaysia, who question the cuisine’s historical credentials, given the country itself is only 53 years old.

But the hawker trade has never been as trendy as it is now. Chan Hon Meng became the celebrity “Hawker Chan” when his soy sauce chicken rice and noodle stall, buried away in Singapore’s Chinatown Complex, caught the eye of Michelin tasters, who awarded their first-ever star to a budget food vendor.

Tourists and locals flocked, queues snaked a quarter-mile round the block, until the food centre’s management told Chan to sort out his new-found fame; it was becoming a fire hazard. Chan thought outside the box of his one stall and brought in outside investors, Singaporean brand agency Hersing, and expanded to become the world’s most famous hawker. All his stores now go under the umbrella “Hawker Chan” chain.

“When I first started in 2009, I was doing it just to make a living, as my last job didn’t pay enough, I have a 12-year-old daughter and a wife. I didn’t even know Michelin existed, but I wanted to serve high quality food,” says Chan, through an interpreter.

“I’m not sure who tried my food at Michelin, but maybe they liked my chicken because it’s better texture and quality, I’m just very lucky they chose me. Once I got the Michelin star it was good and bad – other hawkers were jealous, but it gave them encouragement to be better. It’s proof that a hawker can [have] a successful career, not just earn a living.

Singapore’s got a taste for Hong Kong cooking – and it’s coming back for more

“Now I manage different outlets, there’s a central kitchen doing the core ingredients, then it’s distributed to all the kitchens, and I work hard with all the chefs to maintain consistency and quality.

“Food wasn’t that bad five years ago, but now there are more rewards and recognition from the likes of Michelin. I’m very optimistic for the future.”

The hawker trade wasn’t always this popular. In 2003, the number of stalls had dropped to fewer than 3,000, but in recent years this has surged to nearly 14,000, according to the National Environment Agency.

Thai street food sellers would sigh at Chan’s cheery outlook, as the government is forcefully removing them from the tarmac. In Bangkok’s famous tourist street, Khao San Road, stalls are now not allowed to set up during the day. The tough policy stretches right across the capital.

A whole culture is being swept away, in favour of easing traffic congestion. Other hectic cities such as Ho Chi Minh City and Manila are following suit. There’s been widespread condemnation – The Economist called it “southeast Asian cities waging war on street food” – but any street rebels are threatened with prison.

In some respects, Singapore should be applauded for trying to preserve its hawker industry with Unesco recognition for the 110 food centres dotted around the island, even if critics say that the nation’s signature dishes are really a mishmash of neighbouring countries’ cuisines.

Tandoori momo: how Tibetan refugees reshaped Indian cuisine

Yet Sarah Baker, McDonald’s Asia-Europe Digital Director and a gastronomy masters graduate specialising in Asian street food, claims street food’s extinction is inevitable.

“The street food industry is definitely on the decline. This is mainly due to the older generation retiring and the youth showing less interest in entering the industry due to difficult working conditions with long hours and lower earnings.

“For existing street food vendors, the increased availability of Western food options, societal shifts to healthier eating and extreme price competitiveness between vendors make day-to-day operations challenging. This decline is very unfortunate as it means authentic recipes may start to die out and dilute the overall heritage of the region.”

“I think Singapore is a good example to the rest of Asia. Hawker centres are very well run in terms of hygiene levels. Of course, there is still room for improvement, like our present focus of getting patrons to return their trays and keeping the tables clean after use. But the new hawker centres are certainly very clean and well-ventilated.”

Well done: the Indian vegetarian selling steaks in Hong Kong

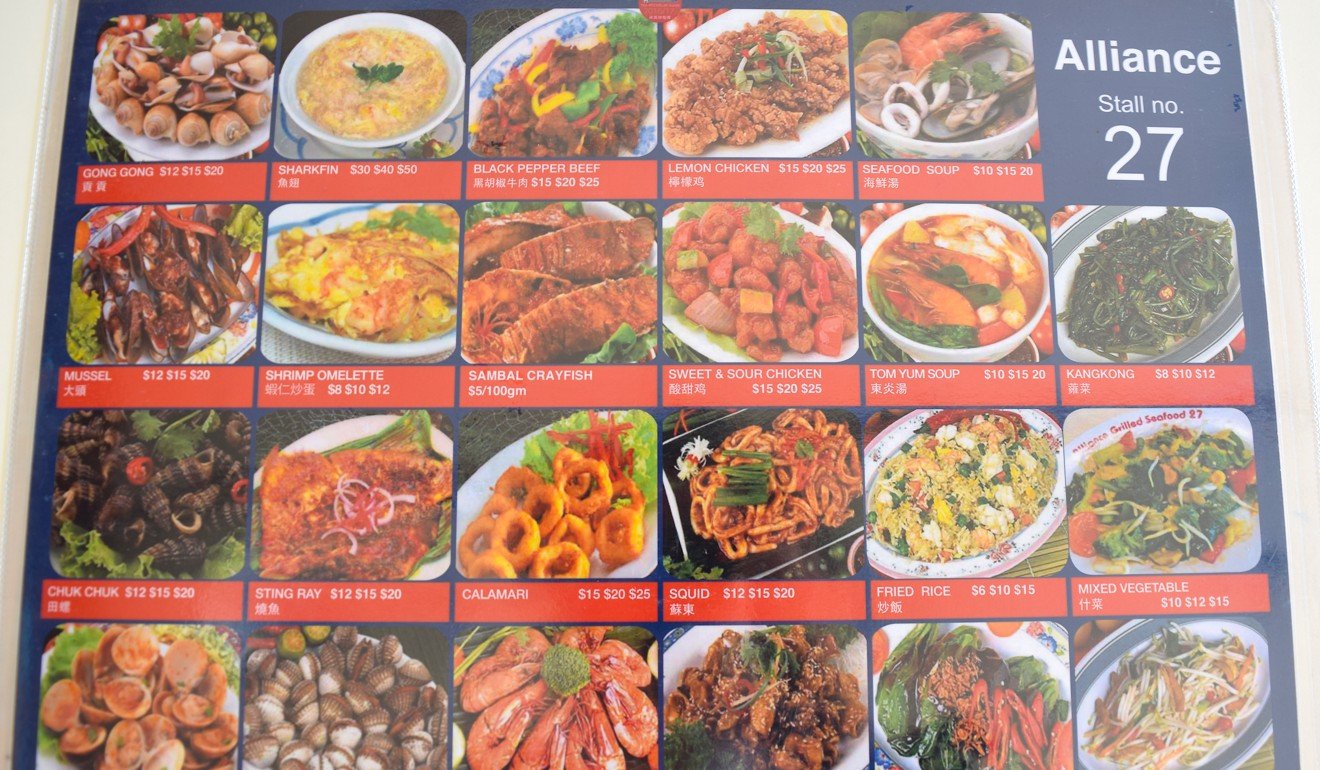

In the nineties, Desmond Ho, 43, along with his brother Richard, took over their father’s hawker stall, Alliance Seafood, at Newton Food Centre, just a mile away from the famous Orchard Road shopping strip. It was at a time when all his friends were going to college and most of them looked down at his choice of work – “they want air con and office hours” he says – but he also had to study.

Twenty years ago, hawkers were definitely not cool, with, literally, boiling hot working conditions, poor financial returns and 16-hour days. Times haven’t changed completely, it’s still hard graft and the cost of owning a stall has shot up tenfold, according to Tay. “Veteran hawkers were paying two to three hundred a month – now it’s S$3,000 (HK$17,000) a month and they have to bid for the space,” he adds.

With higher overheads, vendors are either drowning in cash flow problems, or changing tactic: increase quality and, therefore, cost.

Sichuan cuisine and the red hot secret about globalisation

This year, the Michelin Bib Gourmand Top 50 list of “exceptionally good food at moderate prices”, included 28 hawker stalls, such as the Coconut Club, which serves only two dishes, Nasi Lemak and Cendol dessert, but spent two years creating the perfect recipe. The Ho brothers, relatively young in hawker years, were also on the list and say they do “nothing special”, but it’s always “good quality”.

The industry still struggles to entice youngsters, but those willing to give up their “shirts and ties” to ply a hawker trade now have a dream: to be the next Hawker Chan.

Tay adds: “We are beginning to appreciate what we have on the island, people regard the hawker centre as their bread and butter. Now there are younger people taking familiar flavours, and fusing it into a new form. In the last 10 years we’ve seen an improvement.

“There’s been some progress, hawkers have gone in a different direction and gone for quality instead. A new wave of higher end hawker food. The Michelin guide is helpful, it gives younger ones something to aim for, there’s worldwide recognition.

“Tourists have no prejudice, they don’t feel the hawker centre should be a certain price and usually they will pay a bit more. Michelin-starred ones have more leeway to change the price. It’s about quality control with stock, noodles, vegetables.”

Price is still a huge factor, but more hawker cooks are now classed as gourmet chefs, and a smallish band of more cash-rich consumers don’t mind stretching their wallets. This discerning foodie group is only set to get bigger in the future.

There will be economic casualties, but there’s an inevitability towards the “gentrification” of street food. It is now the hipsters’ choice.

Chan has observed that cooks are now coming from all around Asia to work in Singapore’s hawker industry, but he says it’ll expand even further in the future.

“Everyone knows about the Bangkok street food, but these days, it’s different as governments are getting stricter on the rules, they want it more modernised, centralised, and this is better.

“Singapore should set an example to Thailand and Vietnam, the customer deserves more quality. We are showing that this sort of food can survive. There are many who now come from China, Malaysia and Thailand wanting to learn, we are an example to them.

The Singapore government has launched initiatives to encourage hawkers to be healthier, advertise the nutritional value on each meal, and substitute white for brown rice and noodles. It also wants to make hawkers “cashless” in the near future.

Just three years ago, it would have been pie in the sky to think a hawker could win a Michelin star, now there are two in Singapore – Hawker Chan and Hill Street Tai Hwa Pork Noodle.

Chan believes street food culture has a strong part to play in Asian culture. It’s just about free thinking, quality and hard work. “Over the years, the expectations of customers have gradually risen, they’ll go somewhere else if you’re not providing what they want. They like healthy food. In order to compete, you have to give your best food and creativity is very important,” says Chan.

“It’s important to have a passion in what you’re doing so you’re not affected by competition. You can’t just do the usual thing or you’ll fail. Hawkers have been put on the map by Michelin, now let’s keep it there.” ■